Laborator 3 - Suport teoretic

Instrucțiuni aritmetice

ADC

Sintaxă:

adc <regd>,<regs>; <regd> ← <regd> + <regs> + CF

adc <reg>,<mem>; <reg> ← <reg> + <mem> + CF

adc <mem>,<reg>; <mem> ← <mem> + <reg> + CF

adc <reg>,<con>; <reg> ← <reg> + <con> + CF

adc <mem>,<con>; <mem> ← <mem> + <con> + CF

Semantică și restricții:

- Cei doi operanzi ai adunării trebuie să aibă același tip (ambii octeți, ambii cuvinte, ambii dublucuvinte);

- În timp ce ambii operanzi pot fi regiștri, cel mult un operand poate fi o locație de memorie;

- La suma dintre cei doi operanzi se mai adună şi valoarea bitului de transport (Carry Flag).

Exemplu:

adc EDX,EBX; EDX ← EDX + EBX + CF

adc AX,[var]; AX ← AX + [var] + CF

adc [var],AX; [var] ← [var] + AX + CF

adc EAX,123456h; EAX ← EAX + 123456h + CF

adc BYTE [var],10; BYTE [var] ← BYTE [var] + 10 + CF

SBB

Sintaxă:

sbb <regd>,<regs>; <regd> ← <regd> - <regs> - CF

sbb <reg>,<mem>; <reg> ← <reg> - <mem> - CF

sbb <mem>,<reg>; <mem> ← <mem> - <reg> - CF

sbb <reg>,<con>; <reg> ← <reg> - <con> - CF

sbb <mem>,<con>; <mem> ← <mem> - <con> - CF

Semantică și restricții:

- Cei doi operanzi ai scăderii trebuie să aibă același tip (ambii octeți, ambii cuvinte, ambii dublucuvinte);

- În timp ce ambii operanzi pot fi regiștri, cel mult un operand poate fi o locație de memorie;

- Din diferenţa dintre cei doi operanzi se mai scade şi valoarea bitului de transport (Carry Flag).

Exemplu:

sbb EDX,EBX; EDX ← EDX - EBX - CF

sbb AX,[var]; AX ← AX - [var] - CF

sbb [var],AX; [var] ← [var] - AX - CF

sbb EAX,123456h; EAX ← EAX - 123456h - CF

sbb byte [var],10; BYTE [var] ← BYTE [var] - 10 - CF

IMUL

Sintaxă:

imul <op8>; AX ← AL * <op8>

imul <op16>; DX:AX ← AX * <op16>

imul <op32>; EDX:EAX ← EAX * <op32>Semantică și restricții:

- Rezultatul operației de înmulțire se păstrează pe o lungime dublă față de lungimea operanzilor;

- Instrucțiunea IMUL efectuează operația de înmulțire pentru întregi cu semn;

- Se impune ca primul operand și rezultatul să se păstreze în regiștri;

- Operandul explicit poate fi un registru sau o variabilă, dar nu poate fi o valoare imediată (constantă);

Exemplu:

imul DH; AX ← AL * DH

imul mem8; AX ← AL * mem8

imul DX; DX:AX ← AX * DX

imul EBX; EDX:EAX ← EAX * EBXIDIV

Sintaxă:

idiv <reg8>; AL ← AX / <reg8>, AH ← AX % <reg8>

idiv <reg16>; AX ← DX:AX / <reg16>, DX ← DX:AX % <reg16>

idiv <reg32>; EAX ← EDX:EAX / <reg32>, EDX ← EDX:EAX % <reg32>

idiv <mem8>; AL ← AX / <mem8>, AH ← AX % <mem8>

idiv <mem16>; AX ← DX:AX / <mem16>, DX ← DX:AX % <mem16>

idiv <mem32>; EAX ← EDX:EAX / <mem32>, EDX ← EDX:EAX % <mem32>

Semantică și restricții:

- Instrucțiunea IDIV efectuează operația de împărțire pentru întregi cu semn;

- Se impune ca primul operand și rezultatul să se păstreze în regiștri;

- Primul operand nu se specifică și are o lungime dublă față de al doilea operand;

- Operandul explicit poate fi un registru sau o variabilă, dar nu poate fi o valoare imediată (constantă);

- Prin împărțirea unui număr mare la un număr mic, există posibilitatea ca rezultatul să depășească capacitatea de reprezentare. În acest caz, se va declanșa aceeași eroare ca și la împărțirea cu 0.

Exemplu:

idiv CL; AL ← AX / CL, AH ← AX % CL

idiv SI; AX ← DX:AX / SI, DX ← DX:AX % SI

idiv EBX; EAX ← EDX:EAX / EBX, EDX ← EDX:EAX % EBX

idiv DWORD [var]; EAX ← EDX:EAX / DWORD [var], EDX ← EDX:EAX % DWORD [var]

Instructiuni de conversie cu semn

CBW

Sintaxă:

cbw

Semantică și restricții:

- converteşte cu semn BYTE-ul din AL la WORD-ul AX;

- conversia se referă la extinderea reprezentării de pe 8 biţi pe 16 biţi, prin completarea cu bitul de semn în faţa octetului iniţial;

- instrucţiunea nu are operanzi specificaţi explicit deoarece este întotdeauna vorba despre conversia AL → AX.

Exemplu:

cbw ; dacă AL=01110111b atunci AX ← 00000000 01110111b

; dacă AL=11110111b atunci AX ← 11111111 11110111b

CWD

Sintaxă:

cwd

Semantică și restricții:

- converteşte cu semn WORD-ul din AX la DWORD-ul DX:AX;

- conversia se referă la extinderea reprezentării de pe 16 biţi pe 32 biţi, prin completarea cu bitul de semn în faţa cuvântului iniţial;

- instrucţiunea nu are operanzi specificaţi explicit deoarece este întotdeauna vorba despre conversia AX → DX:AX.

Exemplu:

cwd ; dacă AX=00110011 11001100b atunci DX:AX ← 00000000 00000000 00110011 11001100b

; dacă AX=10110011 11001100b atunci DX:AX ← 11111111 11111111 10110011 11001100b

CWDE

Sintaxă:

cwde

Semantică și restricții:

- converteşte cu semn WORD-ul din AX la DWORD-ul EAX;

- conversia se referă la extinderea reprezentării de pe 16 biţi pe 32 biţi, prin completarea cu bitul de semn în faţa cuvântului iniţial;

- instrucţiunea nu are operanzi specificaţi explicit deoarece este întotdeauna vorba despre conversia AX → EAX.

Exemplu:

cwde ; dacă AX=00110011 11001100b atunci EAX ← 00000000 00000000 00110011 11001100b

; dacă AX=10110011 11001100b atunci EAX ← 11111111 11111111 10110011 11001100b

CDQ

Sintaxă:

cdq

Semantică și restricții:

- converteşte cu semn DWORD-ul din EAX la QWORD-ul EDX:EAX;

- conversia se referă la extinderea reprezentării de pe 32 biţi pe 64 biţi, prin completarea cu bitul de semn în faţa dublucuvântului iniţial;

- instrucţiunea nu are operanzi specificaţi explicit deoarece este întotdeauna vorba despre conversia EAX → EDX:EAX.

Exemplu:

cdq ; dacă EAX=00110011 11001100 00110011 11001100b atunci EDX:EAX ← 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 00110011 11001100 00110011 11001100b

; dacă EAX=10110011 11001100 10110011 11001100b atunci EDX:EAX ← 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 10110011 11001100 10110011 11001100b

Conversie fără semn

Conversie fără semn

- Nu există instrucţiuni de conversie fără semn;

- Conversiile fără semn se realizează în limbajul de asamblare prin „zerorizarea” octetului, cuvântului sau dublucuvântului superior.

Exemple

mov AH,0 ; pentru conversia AL → AX

mov DX,0 ; pentru conversia AX → DX:AX

mov EDX,0 ; pentru conversia EAX → EDX:EAX

Declararea variabilelor / constantelor

Declararea variabilelor cu valoare initiala

a DB 0A2h ;se declara variabila a de tip BYTE si se initializeaza cu valoarea 0A2h

b DW 'ab' ;se declara variabila a de tip WORD si se initializeaza cu valoarea 'ab'

c DD 12345678h ;se declara variabila a de tip DOUBLE WORD si se initializeaza cu valoarea 12345678h

d DQ 1122334455667788h ;se declara variabila a de tip QUAD WORD si se initializeaza cu valoarea 1122334455667788h

Declararea variabilelor fara valoare initiala

a RESB 1 ;se rezerva 1 octet

b RESB 64 ;se rezerva 64 octeti

c RESW 1 ;se rezerva 1 word

Definirea constantelor

zece EQU 10 ;se defineste constanta zece care are valoarea 10

Legendă

<op8> - operand pe 8 biți

<op16> - operand pe 16 biți

<op32> - operand pe 32 biți

<reg8> - registru pe 8 biți

<reg16> - registru pe 16 biți

<reg32> - registru pe 32 biți

<reg> - registru

<regd> - registru destinație

<regs> - registru sursă

<mem8> - variabilă de memorie pe 8 biți

<mem16> - variabilă de memorie pe 16 biți

<mem32> - variabilă de memorie pe 32 biți

<mem> - variabilă de memorie

<con8> - constantă (valoare imediată) pe 8 biți

<con16> - constantă (valoare imediată) pe 16 biți

<con32> - constantă (valoare imediată) pe 32 biți

<con> - constantă (valoare imediată)

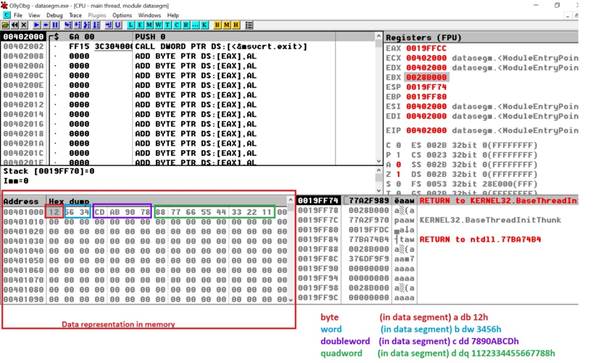

Little endian representation

Theory

- Each byte has an address (the byte being the smallest addressable unit of memory)

- An address identifies in a unique way a location in memory, and x86 processors assign each byte location a separate memory address

- x86 processors store and retrieve data from memory using little endian order (the byte representing the „end” of the number will be stored at the „little”-est address):

- The least significant byte is stored at the beginning of that memory area (at the address where allocation for the data begins).

- The remaining bytes are stored in reverse order in the next consecutive memory positions.

(much more clearer as an informal statement: if we have on paper or in a register a 4 bytes number and we denote the order of these bytes as 1 2 3 4 , in the memory the little-endian representation will store that number in the reverse order of its bytes: 4 3 2 1).

Careful ! – only the BYTES order is reversed in memory, NOT the BITS inside that bytes !!!!! The order of the bits which compose each byte remains the same !

For instance, if we have the following data segment:

a db 12h

b dw 3456h

c dd 7890abcdh

d dq 1122334455667788h Data representation in memory will be as shown in the lowest left corner from the below debugger configuration:

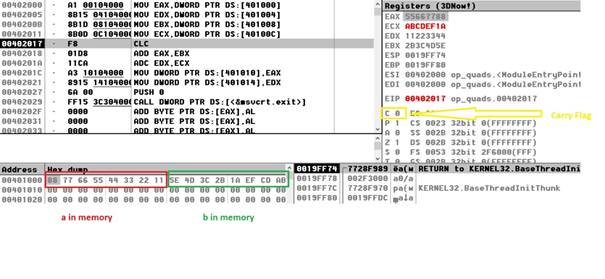

Example 1: Addition: quadword+quadword

bits 32 ;assembling for the 32 bits architecture

; the start label will be the entry point in the program

global start

extern exit ; we inform the assembler that the exit symbol is foreign, i.e. it exists even if we won't be defining it

import exit msvcrt.dll; exit is a function that ends the process, it is defined in msvcrt.dll

; msvcrt.dll contains exit, printf and all the other important C-runtime functions

segment data use32 class=data ; the data segment where the variables are declared

a dq 1122334455667788h

b dq 0abcdef1a2b3c4d5eh

r resq 1 ; reserve 1 quadword in memory to save the result

; our code starts here

segment code use32 class=code ; code segment

start:

;11223344 55667788 h -> EDX : EAX

; EDX : EAX

mov eax, dword [a+0]

mov edx, dword [a+4]

; abcdef1a 2b3c4d5e h -> ECX : EBX

; ECX : EBX

mov ebx, dword [b+0]

mov ecx, dword [b+4]

;a + b

; edx : eax +

; ecx : ebx

clc ; clear Carry Flag (punem 0 in CF)

add eax, ebx ; eax= eax+ebx

adc edx, ecx ; edx = edx+ecx + CF

;(CF is set is add eax, ebx produce a carry)

;edx:eax -> r

mov dword [r+0], eax

mov dword [r+4], edx

push dword 0 ; push the parameter for exit onto the stack

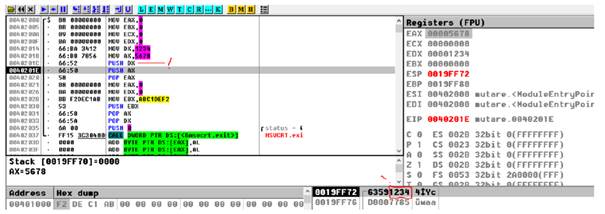

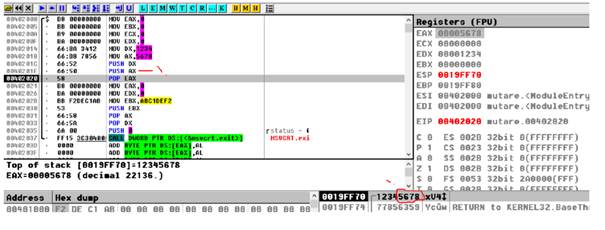

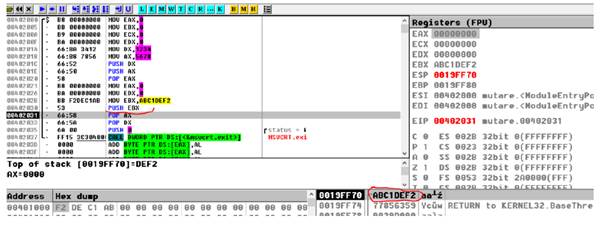

call [exit] ; call exit to terminate the programStep 1 – before perform the addition

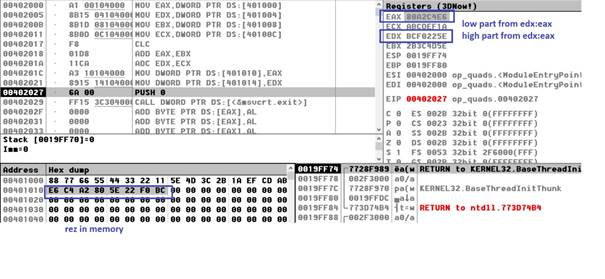

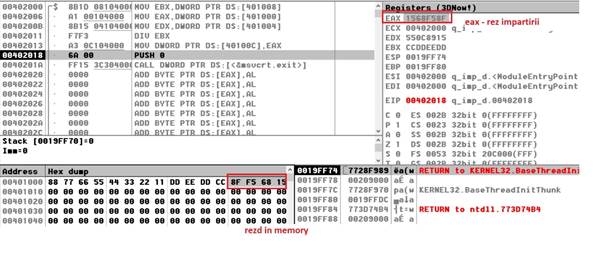

Example 2. Division: quadword/doubleword

bits 32 ;assembling for the 32 bits architecture

; the start label will be the entry point in the program

global start

extern exit ; we inform the assembler that the exit symbol is foreign, i.e. it exists even if we won't be defining it

import exit msvcrt.dll; exit is a function that ends the process, it is defined in msvcrt.dll

; msvcrt.dll contains exit, printf and all the other important C-runtime functions

segment data use32 class=data ; the data segment where the variables are declared

m dq 1122334455667788h

n dd 0ccddeeddh

rezd resd 1

; our code starts here

segment code use32 class=code ; code segment

start:

mov ebx, [n]

;11223344 55667788 h -> EDX : EAX

; EDX : EAX

mov eax, dword [m+0]

mov edx, dword [m+4]

div ebx ; edx:eax/ebx=eax cat si edx rest

mov dword[rezd], eax

push dword 0 ; push the parameter for exit onto the stack

call [exit] ; call exit to terminate the program

Stack in assembly

Theory

- The runtime stack is a memory array managed directly by the CPU, using the ESP register, known as the stack pointer register.

- The ESP register holds a 32-bit offset into some location on the stack. We rarely manipulate ESP directly; instead, it is indirectly modified by instructions such as CALL, RET, PUSH, and POP.

- ESP always points to the last value to be added to, or pushed on, the top of stack.

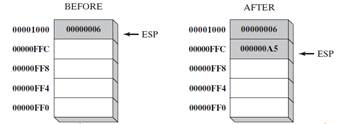

- In Figure 1, the ESP (extended stack pointer) contains hexadecimal 00001000, the offset of the most recently pushed value (00000006).

- In our diagrams, the top of the stack moves downward when the stack pointer decreases in value:

- Each stack location in this figure contains 32 bits, which is the case when a program is running in 32-bit mode. In 16-bit real-address mode, the SP register points to the most recently pushed value and stack entries are typically 16 bits long.

PUSH Operation

- A 32-bit push operation decrements the stack pointer by 4 and copies a value into the location in the stack pointed to by the stack pointer.

- Figure 2 shows the effect of pushing 000000A5 on a stack that already contains one value (00000006). Notice that the ESP register always points to the top of the stack.

- The figure shows the stack ordering opposite to that of the stack of plates we saw earlier, because the runtime stack grows downward in memory, from higher addresses to lower addresses. Before the push, ESP = 00001000h; after the push, ESP = 00000FFCh.

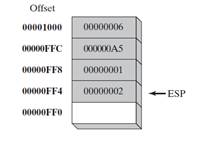

- Figure 3 shows the same stack after pushing a total of four integers.

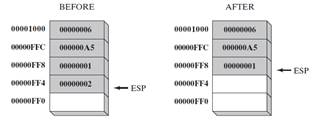

POP Operation

- A pop operation removes a value from the stack. After the value is popped from the stack, the stack pointer is incremented (by the stack element size) to point to the next-highest location in the stack.

- Figure 4 shows the stack before and after the value 00000002 is popped.

- The area of the stack below ESP is logically empty, and will be overwritten the next time the current program executes any instruction that pushes a value on the stack.

Stack Applications

- A stack makes a convenient temporary save area for registers when they are used for more than one purpose. After they are modified, they can be restored to their original values.

- When the CALL instruction executes, the CPU saves the current subroutine’s return address on the stack.

- When calling a subroutine, you pass input values called arguments by pushing them on the stack.

- The stack provides temporary storage for local variables inside subroutines.

PUSH and POP Instructions

PUSH Instructions

The PUSH instruction first decrements ESP and then copies a source operand into the stack.A 16-bit operand causes ESP to be decremented by 2. A 32-bit operand causes ESP to be decremented by 4. There are three instruction formats:

PUSH reg/mem16

PUSH reg/mem32

PUSH imm32POP Instructions

The POP instruction first copies the contents of the stack element pointed to by ESP into a 16- or 32-bit destination operand and then increments ESP. If the operand is 16 bits, ESP is incremented by 2; if the operand is 32 bits, ESP is incremented by 4:POP reg/mem16

POP reg/mem32PUSHFD and POPFD Instructions

- The PUSHFD instruction pushes the 32-bit EFLAGS register on the stack, and POPFD pops the stack into EFLAGS:

pushfd

popfd- 16-bit programs use the PUSHF instruction to push the 16-bit FLAGS register on the stack and POPF to pop the stack into FLAGS.

- in 32 bits programming both PUSHF and PUSHFD can be used in order to push the 32-bit EFLAGS on the stack

- The MOV instruction cannot be used to copy the flags to a variable, so PUSHFD may be the best way to save the flags. There are times when it is useful to make a backup copy of the flags so you can restore them to their former values later. Often, we enclose a block of code within PUSHFD and POPFD:

pushfd ; save the flags

;

; any sequence of statements here...

;

popfd ; restore the flags- When using pushes and pops of this type, be sure the program’s execution path does not skip over the POPFD instruction. When a program is modified over time, it can be tricky to remember where all the pushes and pops are located.

The need for precise documentation is critical!

A less error-prone way to save and restore the flags is to push them on the stack and immediately pop them into a variable:

.data

saveFlags DW 0

.code

pushfd ; push flags on stack

pop saveFlags ; copy into a variable- The following statements restore the flags from the same variable:

push saveFlags ; push saved flag values

popfd ; copy into the flagsPUSHAD, PUSHA, POPAD, and POPA

- The PUSHAD instruction pushes all of the 32-bit general-purpose registers on the stack in the following order:

EAX, ECX, EDX, EBX, ESP (value before executing PUSHAD), EBP, ESI, and EDI. - The POPAD instruction pops the same registers off the stack in reverse order.

- Similarly, in 16 bits programs the PUSHA instruction, introduced with the 80286 processor, pushes the 16-bit generalpurpose registers (AX, CX, DX, BX, SP, BP, SI, DI) on the stack in the order listed.

- The POPA instruction pops the same registers in reverse order.

- in 32 bits programming POPA and POPAD, respectively PUSHA and PUSHAD have the same behavior

If you write a procedure that modifies a number of 32-bit registers, use PUSHAD at the beginning of the procedure and POPAD at the end to save and restore the registers. The following code fragment is an example:

pushad ; save general-purpose registers

.

.

mov eax,...

mov edx,...

mov ecx,...

.

.

popad ; restore general-purpose registers- An important exception to the foregoing example must be pointed out; procedures returning results in one or more registers should not use PUSHA and PUSHAD.

- Suppose the following ReadValue procedure returns an integer in EAX; the call to POPAD overwrites the return value from EAX:

ReadValue PROC

pushad ; save general-purpose registers

.

.

mov eax,return_value

.

.

popad ; overwrites EAX!

ret

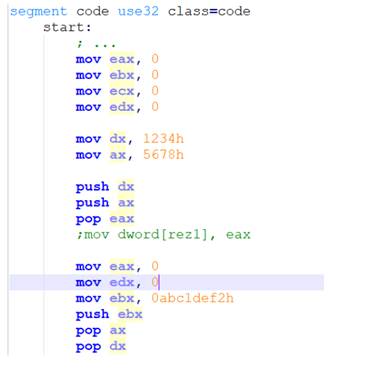

ReadValue ENDPExamples

- Unlike the ESP register, the base pointer EBP is manipulated only explicitly.

- EBP is used by high-level languages to reference function parameters and local variables on the stack. It should not be used for ordinary arithmetic or data transfer except at an advanced level of programming. It is often called the extended frame pointer register.

- EBP role will be clarified in the last courses of the semester when the integration of Assembly Language with high level programming languages (namely C in our case) will be studied. But, a few words on the role of the EBP and ESP stack registers in the functioning of the run time stack can be said at this moment also, considering only an ASM code to implement a function, concept recognized only by a high-level programming language.

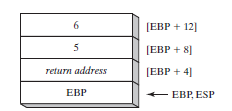

- A new procedure/function that is called will become the currently executing subroutine, so in the run time stack a new stackframe must be built for this subroutine. This new stackframe will be delimited by the EBP (at the basis) and the ESP (at the top) stack pointer registers, so the values from EBP and ESP must be updated for adapting to the new subroutine context.

- But, for being able after the call to return to the caller, the caller’s stackframe must be restored, so the current (”old”) EBP value for the caller has to be saved. This is done as the first thing by the new called subroutine, which saves IN THE STACK using a PUSH EBP the base address of the caller’s stackframe. After that, the EBP value can be updated to point to the beginning of the new stackframe (mov ebp,esp), which will be exactly the location shown by ESP, so the new stackframe will start with the value of the „old” EBP. So, in this point EBP and ESP have both the same value (indicating that the new stackframe is empty and ready to receive the required data to „grow” and start the execution of the current subroutine.

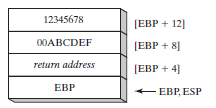

- This mechanism is briefly illustrated below in the case of a procedure called AddTwo which will add the values of the two passed parameters and returns their sum in EAX:

AddTwo:

push ebp; saving the caller’s stackframe base for further being able to restore it

mov ebp,esp ; initialising the base of the new stack frame for the currently executing

; procedure AddTwo (see the picture below which illustrates exactly

; this described situation)

mov eax,[ebp + 12] ; transferring into EAX the value of the second parameter passed

; on to the stack by the caller BEFORE the new stackframe takes

; the run time control

add eax,[ebp + 8] ; adding to EAX the first parameter

pop ebp ; restoring the caller stackframe as being the new currently executing one

ret ; going back immediately to the point of call for continuing the execution

; of the program

Stack Frame after Pushing EBP and ESP value was copied to EBP:

After the next two instructions (mov and add) execute, the following figure shows the contents of the stack frame: a function call such as AddTwo(5, 6) would cause the second parameter to be pushed on the stack, followed by the first parameter:

AddTwo could push additional registers on the stack without altering the offsets of the stack parameters from EBP. ESP would change value, but EBP would not.